skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Today's post is an excerpt from the book Wedding Photographer's Handbook (2nd ed.) It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.Since the bride and groom are so preoccupied at the reception, they actually get to see very little of it and therefore depend on your pictures to provide memories. You will want to photograph as many of the details and events of the reception as possible. Be sure to make several good overviews of the decorated room. This should be done just before the guests enter, when the candles on the tables are lit and everything looks perfect.

Be sure to photograph the details—table bouquets, place settings, name cards, etc. These things help enrich the finished wedding album.

The photo opportunities at the reception are endless. As the reception goes on and guests relax, the opportunities for great pictures will increase. Be aware of the bride and groom all the time, as they are the central players. Fast lenses and a higher-than-normal ISO settings will help you to work unobserved.

Be prepared for the scheduled events at the reception—the bouquet toss, removing the garter, the toasts, the first dance, and so on. If you have done sufficient preparation, you will know where and when each of these events will take place and you’ll be prepared to light and photograph each one. Often, the reception is best lit with a number of corner-mounted umbrellas, triggered by your on-camera flash. That way, anything within the perimeter of your lights can be photographed by strobe. Be certain you meter various areas within your lighting perimeter so that you know what your exposure will be everywhere within the reception area.

The reception calls upon all of your skills and instincts—and things happen quickly. Don’t get caught with an important event coming up and only two frames left in the camera. Use two camera bodies and always have plenty of exposures available, even if it means changing CF cards before you’re ready to. People are having a great time, so be cautious about intruding upon events. Observe the flow of the reception and carefully choose your vantage point for each shot. Be sure to coordinate your efforts with the wedding planner or banquet manager. He or she can run interference for you as well as cue you when certain events are about to occur, often not letting the event begin until you are ready.

Photojournalists know how to get the shot without alerting the people being photographed. Some photographers walk around the reception with their camera held low but with both hands in position on the camera so that they can instantly raise the camera to eye level, frame the image, and shoot. Others use a wide-angle lens set to wide-area autofocus in one of the camera’s autoexposure modes. With the camera at waist or hip height, the photographer will then wander around, mingling with the guests. When a shot seems to be taking place, they will aim the camera up toward the people’s faces and fire, never even looking through the viewfinder.

The final shot of the day will be the couple leaving the reception. Like so many events at the reception, planned or spontaneous, it is best to have as many angles of the event as possible, which is why so many wedding photographers work with a shooting partner or assistants.

LIGHTING

Pole Lighting. Many photographers employ an assistant at the reception to walk around with a barebulb flash on a monopod. The strobe is slaved and can be triggered by an on-camera radio transmitter or flash. The pole light can be positioned anywhere near the subjects and can be set to overpower the on-camera flash by 1 stop so that it becomes a main light. Your assistant should be well versed in the types of lighting you like to create with this rig. For instance, if he or she is at a 45-degree angle to the subject and the light is held about four feet over the subjects’ head height, the resulting lighting will resemble Rembrandt-style side lighting. If you prefer to backlight your subjects, then your assistant can position himself behind the group to create a rim-lighting effect. When taking an exposure, read the room light first and set the flash output to the same aperture as the existing light exposure. That way, the flash will not overpower the room lights.

Wide-angle lenses are not only ideal for incorporating large groups in the scene but also for incorporating the scene into the portrait. This image was made with a Canon EF17–40mm f/4L USM at 17mm. The photographer, Dan Doke, says of this image, “I had been photographing a wedding party and posed a group adjacent to the New England Aquarium where the wedding was held. I was drawn to the skyline background. With my camera on a tripod I shot in Av mode and varied the aperture from f/5.6 to f/8. The exposure time was 1.3 seconds at ISO 500. I used a Quantum flash with a Freewire slave. My assistant held the second light and umbrella 45 degrees off to the right and feathered it to create a constant exposure. The flash was set for f/5.6 and I shot a test first. I love it when city lights and the sky are about the same intensity.” Note the total lack of distortion of the subjects by keeping them well away from the frame edges.

Videographer’s Lighting. If a wedding video is being produced, you will have the luxury of the videographer rigging and lighting the reception hall with hot lights—usually quartz halogen lights, which are very bright and will make your reception photography much easier. The only problem is that you will have to adjust your white balance to compensate for the change in color temperature of the quartz lights.

Handheld Video Lights. Many of the Australian wedding photographers, like David Williams and Yervant, use handheld battery-powered video lights as accent or fill lights. Williams uses a low-wattage light, around 15–20 watts, for just a little light to add mood or color or accent to a scene. Yervant uses a 100-watt Lowel Light that will overpower the room light, depending on the distance at which it is used. The effects are quite beautiful and, because you can change your white balance on the fly, the color balance will be superb and match the room lighting. Sometimes the photographers will hold the light themselves, and other times they’ll give it to an assistant if a certain lighting effect is desired. One of the great things about these lights is that you can see the effect you will get in the viewfinder. Also, since the light units are small and maneuverable, you can feather them easily, using the more dynamic edge of the light.

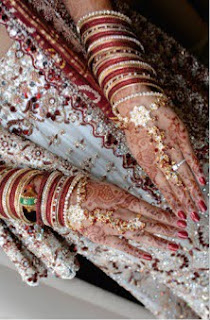

RINGS

The bride and groom usually love their new rings and will want a close-up shot that includes them. This is a great detail image in the album. You can use any attractive pose, but remember that hands are difficult to pose. If you want a really close-up image of the rings, you will need a macro lens and you will probably have to light the scene with flash or video light, unless you make the shot outdoors, in strong window light, or using strong available room light.

The ring exchange during the wedding ceremony is very difficult to capture. Having two shooters helps, but even then you might get blocked out by the bride, groom, or minister. This is a good one, indeed. Photo by Nick Adams.

THE CAKE-CUTTING

One of the key shots at the reception is the cutting of the wedding cake. This is often a good opportunity to make an overhead group shot of the crowd surrounding the bride and groom. Bring along a stepladder for these types of shots. A second shooter is a good idea in these situations so that details and priceless moments won’t be missed. Also, be sure to get a still life of the cake before it is cut. Both the couple and the baker/caterer will want to see a beautiful shot of their creation.

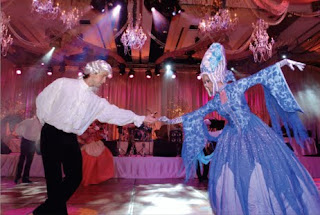

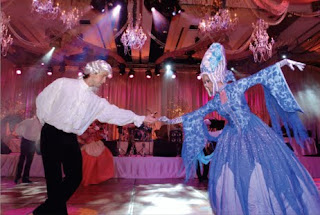

THE FIRST DANCE

The first dance is an important moment in the reception and one that you will want to document thoroughly. Don’t turn it into a cliché. Just observe and try to shoot it with multiple shooters so as not to miss the good expressions. You will be rewarded with emotion-filled, joyful moments.

One trick you can use is to tell the couple beforehand, “Look at me and smile.” That will keep you from having to circle the couple on the dance floor until you get both of them looking at you for the “first dance” shot. Or you can tell them, “Just look at each other and don’t worry about me, I’ll get the shot.”

Often, photographers will photograph the first dance by whatever available light exists (often spotlights) on the dance floor. This is possible with fast lenses and fast ISOs. Just as frequently, the photographer will use bounce flash and a slow shutter speed to record the ambient light in the room and the surrounding faces watching the couple’s first dance. The bounce flash will freeze the couple, but there is often some blurring due to the slow shutter speed.

Usually, it is best to photograph the first dance as a vertical, including some of the dance floor and surroundings for ambience.

THE BOUQUET TOSS

The bouquet toss is one of the more memorable shots and always looks best when it’s spontaneous. You need plenty of depth of field, which almost dictates a wide-angle lens. You’ll want to show not only the bride but also the expectant faces in the background, which usually necessitates two shooters. Although you can use available light, the shot is usually best done with two flashes—one on the bride and one on the ladies hoping to catch for the bouquet. Your timing has to be excellent as the bride will often “fake out” the group (and you), just for laughs. Try to get the bouquet as it leaves the bride’s hands.

The bouquet toss is often filled with trickery as the bride tries to “fake out” the ladies behind her. Here, Mark Cafiero captured a lovely bride in the middle of a belly laugh. Mark fired a bounce flash at the bride and relied on enough ambient light to light the waiting young brides-to-be. Mark made the shot with a Canon EOS 20D and 24mm lens at 1/50 second at f/3.5 at ISO 400 with the bounce flash held slightly to camera right. Mark was standing on a chair to get above the scene for a better overall view.

TABLE SHOTS

Table shots are the bane of every wedding photographer’s day. They rarely turn out well, are often never ordered, and are tedious to make. If your couple absolutely wants table shots, ask them to accompany you from table to table. They can greet their guests, and it will make the posing quick and painless. You might also consider talking the couple into one big group shot that encompasses nearly everyone at the reception. These are always fun to participate in and to photograph.

LITTLE ONES

One of the best opportunities for great pictures comes from spending some time with the smallest attendees and attendants: the flower girls and ring bearers. They are thrilled with the pageantry of the wedding day and their involvement often offers a multitude of picture opportunities.

The little ones are especially fragile on the wedding day and will present some wonderful photo opportunities. Photograph by Marcus Bell.

Today's post is an excerpt from the book Brett Florens' Guide to Photographing Weddings. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.Once you have sent your quote to a potential client, more often than not they will want to meet with you to have a hands-on look at a portfolio, perhaps a completed album, and also to suss out whether they feel comfortable with you as a person or not. This is where you need to close the deal. They already know what you propose to charge and have probably seen your online portfolio. It’s your approach, ideas, and personality that are going to get them to sign on the dotted line and pay the deposit.

Available light, ISO 400 f/5.6 at 1/125 second, M mode, Nikkor 70–200mm f/2.8 lens. Carefree and dreamy, the engagement session captures the day-to-day romance that is felt between couples about to be wed.

Remember that you will be spending a lot of time with this couple on their day; being friendly, engaging, and taking time to listen to their needs and questions should make them feel comfortable being around you. A photographer who seems arrogant and unfriendly will not be a popular choice—no matter how brilliant his images may be. Dedicate at least an hour to this meeting, and don’t take calls or chat to other clients during this time. It is important to make them feel that they are the only clients you’ve ever had. They must feel that their wedding is as important to you as it is to them. Be careful not to oversell yourself; they are there because they already like your work, so it is unnecessary to go on about how fantastic your work is! Of course, on the other end of the scale, you need to appear to be confident and enthusiastic about your images. Showing them a recently completed album should solidify their confidence in your ability to produce a hot-shot album from start to finish; they’ll know that they are not being fooled by a portfolio of thirty outstanding shots from, perhaps, a choice of a hundred different weddings.

Interact with your clients and show a real interest in their choice of wedding venue and the other suppliers that they have chosen. Let them know if you have worked at their proposed venue before and, if possible, show them images of previous weddings at that venue. This is also an opportunity to show them other peripheral products such as framed images, canvases, and various album choices; these might become add-ons to the package that they choose.

Once the couple have decided to employ you to photograph their wedding, you may want to plan an additional meeting closer to the date to discuss timing and finer details. Discuss, and even advise, the time of the service relative to sunset, as well as the timing of hair and makeup prior to your arrival, letting the client know how far you expect them to be ready when you get to them. I like to have at least an hour and a half with the bride before the ceremony, and I require that she is 80 percent ready when I get to the venue where she is getting dressed. This means that she needs to make sure in advance that the hairdresser and makeup artist will not leave her for last. It is pointless for the photographer to arrive before the ceremony when all he can photograph is a stressed bride in curlers! Inquire as to whether the groom requires preparation shots, too. More often than not, the groom and his best men have something relaxing planned for the morning of the wedding, be it surfing, golfing, or quad-biking. If the package allows the time, these are great shots to add depth to the album.

Make sure that you get all the contact details from the bride and groom, as well as their parents’ details if possible. It is also useful to have the details of all the other vendors that you will be working with. After a few years in the business, you will have the inside scoop on which vendors are always running late, which are pedantic about time, and what their work is like.

Also important to discuss with the bridal couple are their expectations with regard to the images that they want shot. Going through your portfolio together, they will give you a feel as to what images they would ideally like. This is also a good time to choose the venue for the bridal shoot, obviously within a reasonable proximity to the reception venue.

Explain to them, at this stage, that good images do take a certain amount of time and that time management on the wedding day is important. Chatting too long after the service with guests, while the light is fading fast, will necessitate a nudge from you. It’s good to let them know that you will help them to stick to a schedule to optimize the opportunity for outstanding images. The bridal shoot is usually in the region of one hour, and allowances for this must be made prior to the wedding so that the couple ensures that guests are entertained with cocktails or snacks during the time that they are away from them.

Elinchrom 600RX Monolight, ISO 100, f/11 at 1/125 second, M mode, Nikkor 24–70mm f/2.8 lens. From the same engagement shoot as the image on the previous page, this shot shows a completely different side of the couple, expressing their interest in fashion and editorial-style images.

You will need to inform them of the postproduction process, which will involve image enhancement, color management, conversion of raw images, the resizing of images for printing, and the construction of the album. Give them a timeline for when they can expect the finished product. If they are going to be involved in the choosing of the images for the album, then appointments must be made. Bear in mind that client involvement may increase production time and should be incorporated into your costs.

Closer to the day of the wedding, you may be expected to deal with phone calls from an anxious bride needing answers to a dozen questions. Obviously, this is also a time to put the bride at ease and confirm her feeling of confidence in you. You also may be asked to attend the rehearsal at the church. If you feel that you want to charge for your time at this rehearsal, then you must make it known before attending. At an early stage in your career, it may be beneficial to attend; the rehearsals are often set for the same time of day as the ceremony, so you will have a good opportunity to see what the lighting conditions are like and to scout out the ceremony venue for photo opportunities.

Buy this book from Amazon.

Today's post is an excerpt from the book Existing Light Techniques for Wedding and Portrait Photography, by Bill Hurter. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

Nature provides every lighting variation imaginable—that’s why so many images are made with it. Often, the light is so good that there is just no improving on it.

For example, I used to work for a major West Coast publishing company that specialized in automotive magazines. One of the studios we used for photographing cars was massive, with a ceiling that was between three and four stories high. Below the ceiling was a giant scrim suspended on cables so that each of the four corners could be lowered or raised independently. Enormous banks of incandescent lights were bounced into the scrim to produce a huge milky-white highlight the length of the car—a trademark of automotive photography. Despite the availability of this space, if time and the weather were on their side, the staff photographers would invariably opt to photograph the car at twilight, when the setting sun, minutes after sunset, creates a massive skylight in the Western sky. No matter how big or well equipped the studio, nature’s light is far superior in both quantity and quality (although it fades rather quickly).

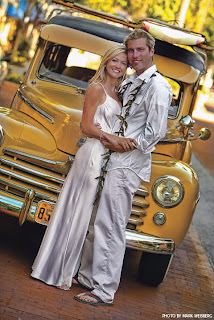

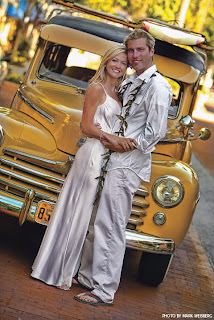

This is the classic Southern California wedding portrait, complete with the kelp necklace on the surfer groom. The light is exquisite because there are buildings to either side blocking the overhead light. The color coordination is also perfect. Photo by Mark Weisberg.

In order to harness the power of natural light, one must be aware of its various personalities. Unlike the studio, where you can set the lights to obtain any effect you want, in nature you must use the light that you find or find ways to modify it to suit your needs.

Avoid Direct Sunlight

By far the best place to make outdoor images is away from direct sunlight. Look for a clearing in the woods, where the trees block the overhead light from hitting the subject. From the clearing to the side, diffused light will filter in, producing better modeling on the face than in an open area (where the light is overhead in nature and leaves deep shadows in the eye sockets and under the nose and chin of the subjects).

Kevin Jairaj, who makes it a habit to look for good directional lighting, recommends looking for an outdoor portico, where light from above is blocked by a roofline or other architectural elements. This allows soft directional light to spill in from the sides, usually through open columns that provide beautiful compositional elements. Depending on how you position your subjects in relation to this directional light, it can be frontal or side-lighting—but it always has a singular and well-defined source point. Kevin says, “When outdoors, I love shooting under awnings or building tops where I am able to see the light coming in from one side. I normally place the bride so that her face is turned into the directional light producing soft Rembrandt lighting on her face.”

Midday light doesn't have to be harsh, especially where tall buildings block the direct light. The lighting is, however, still overhead in such situations. Knowing this helped Mike Cólon, who waited until the bride's head was raised, taking advantageof the soft overhead light.

Working at Midday

Working at midday is a necessity for wedding photographers, as most ceremonies are during the middle of the day.

The best system if working at midday is to work in shade exclusively. Try to find locations where the background has sunlight on dark foliage and where the difference between the background exposure and the subject exposure is not too great—no more than 2.5 stops.

Fuzzy Deunkel is a master of working in any lighting situation. For this image, he posed his subject on a front porch and and masterfully redirected light onto his subject, making it look as though she was photographed in a studio with a full complement of lights.

It is often impossible to avoid photographing out in the open sunlight on wedding days. In this case, the best strategy is to use the sun as a backlight and bias the exposure towards the shadow side(s) of the subject(s). This is where it’s advisable to bring along an assistant who can flash a reflector into the shadow side of your couple to fill in the effects of the backlighting. A reflector is most effective when held below waist height and angled to bounce the overhead backlight back up onto the subject. Moving the reflector around and up and down will give you an idea of how much light it can reflect and where to position it. In bright situations, use a white reflector, so as not to overpower the natural light. In very soft light, use a gold or silver reflector for increased efficiency.

It is important to check the background while composing a portrait in direct sunlight. Since there is considerably more light than in a portrait made in the shade, the tendency is to use an average shutter speed like 1/250 second with a smaller-than-usual aperture like f/11. Small apertures will sharpen the background and distract from your subject. Preview the depth of field to analyze the background. Use a faster shutter speed and wider lens aperture to minimize background effects in these situations. The faster shutter speeds may also make it impossible to use flash, so have reflectors at the ready.

Low-Angle Sunlight

If the sun is low in the sky, you can use cross lighting to get good modeling on your subject. To do this, simply turn your subject into the light so as not to create deep shadows along laugh lines and in eye sockets. (Note: If photographing a group, be sure to position your subjects so that one person’s head doesn’t block the light from striking the face of the person next to him or her.) In this scenario, there must be adequate fill-in from the shadow side of camera to ensure that the shadows don’t go dead. This is often done using a flash set to about a stop less than the daylight exposure. Of course, a reflector can also be employed (and carefully placed) to bounce the direct sunlight back into the shadow side of the face. Again, it’s always best to use an assistant in this situation.

After Sunset

As many of the great photographs in this book illustrate, the best time of day for making great pictures is just after the sun has set. At this time, the sky becomes a huge softbox and the effect of the lighting on your subjects is soft and even, with no harsh shadows.

There are, however, two problems with working with this great light. First, it’s dim. You will need to use medium to fast ISOs combined with slow shutter speeds. In these situations, selecting an image-stabilization lens will expand your options by allowing you to handhold at extremely slow shutter speeds like 1/4 or 1/8 second.

The second problem in working with this light is that twilight does not produce catchlights, the white specular highlights in the eyes of the subjects that make them sparkle with life. For this reason, most photographers augment the twilight with flash, either barebulb or softbox-mounted. The flash can be up to two stops less in intensity than the skylight and still produce good eye fill-in and bright catchlights.

Controlling the Background

For a portrait made in the shade, the best type of background is monochromatic. If the background is all the same color, the subjects will stand out from it. Problems arise when there are patches of sunlight in the background. To minimize these, you can shoot at a wide lens aperture and use the shallow depth of field to blur out the background. When working outdoors, some photographers also control the background by placing more space between it and the subject, throwing the background further out of focus.

Another way to minimize a distracting background is in postproduction retouching and printing. By burning-in or diffusing the background, you can make it darker, softer, or otherwise less noticeable. This technique is really simple in Photoshop, since it’s fairly easy to select the subjects, invert the selection so that the background is selected, and perform all sorts of manipulations on it. You can also add a vignette of any color to visually subdue the background. On outdoor shoots in particular, one thing you must especially watch out for is subject separation from the background. A dark-haired subject against a dark-green forest background will not separate, creating a tonal merger. Adding a back-side or edge reflector to kick some light onto the hair would be a logical solution to such a problem.

Cool Skin Tones

If your subject is standing in a grove of trees and is surrounded by foliage, there is a good chance green (or cyan from the open sky) will be reflected onto their skin tones. This can be hard to detect, since your eyes will adjust to the off-color rendering. The best strategy is to check the coloration in the shadow areas of the face. If the color of the light is neutral, you will see gray in the shadows; if not, you will see either green or cyan.

Buy this book from Amazon

Today's post is an excerpt from the book Wedding Photography: Advanced Techniques for Digital Photographers, by Bill Hurter. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.

BROAD AND SHORT LIGHTING

There are two basic types of portrait lighting: broad lighting and short lighting. Broad lighting means that the main light is illuminating the side of the face that is turned toward the camera. Broad lighting is used less frequently than short lighting because it flattens and de-emphasizes facial contours. It is often used to widen a thin or long face. Short lighting means that the main light is illuminating the side of the face turned away from the camera. Short lighting emphasizes facial contours and can be used to narrow a round or wide face. When used with a weak fill light, short lighting produces a dramatic effect with bold highlights and deep shadows.

BASIC PORTRAIT LIGHTING SETUPS

While it may prove difficult or even impossible to replicate any one of the five basic portrait lighting setups on the day of the wedding, it is still a good idea to know what they are and how to achieve them. Each of the lighting patterns takes its personality from the placement of the main light. The concept of single-source lighting is important. The sun is the primary light source in all of nature; all other light sources are subordinate to it. This is the rule of the main light in the studio; like the sun, it is the single light to which any other lights are subordinate.

Paramount Lighting. Paramount lighting, sometimes called butterfly lighting or glamour lighting, is a lighting pattern that produces a symmetrical, butterfly-shaped shadow directly beneath the subject’s nose. It emphasizes cheekbones and good skin. It is generally not used on men because it tends to hollow out cheeks and eye sockets too much.

For this style, the main light is placed high and directly in front of the subject’s face, parallel to the vertical line of the subject’s nose. Since the light must be high and close to the subject to produce the wanted butterfly shadow, it should not be used on women with deep eye sockets, or very little light will illuminate the eyes.

The fill light is placed at the subject’s head height directly under the main light. Since both the main and fill lights are on the same side of the camera, a reflector must be used opposite these lights and in close to the subject to fill in the deep shadows on the neck and shaded cheek. The hair light, which is always used opposite the main light, should light the hair only and not skim onto the face of the subject. The background light, used low and behind the subject, should form a semi-circle of illumination on the seamless background (if using one) so that the tone of the background grows gradually darker toward the edges of the frame.

Loop Lighting. Loop lighting is a minor variation of Paramount lighting. The main light is lowered and moved more to the side of the subject so that the shadow under the nose becomes a small loop on the shadow side of the face. This is one of the more commonly used lighting setups and is ideal for people with average, oval-shaped faces.

Loop lighting is an intermediate pattern between butterfly and Rembrandt lighting. The main light is high and to one side of the model’s face, but not as high as in the butterfly pattern, nor as low as in the Rembrandt pattern. Here no fill light was used in order to keep the light dramatic. Photograph by JB Sallee.

Loop lighting is an intermediate pattern between butterfly and Rembrandt lighting. The main light is high and to one side of the model’s face, but not as high as in the butterfly pattern, nor as low as in the Rembrandt pattern. Here no fill light was used in order to keep the light dramatic. Photograph by JB Sallee.

The fill light is moved to the opposite side of the camera from the main light in loop lighting. It is used close to the camera lens. In order to maintain the one-light character of the portrait, it is important that the fill light not cast a shadow of its own. To determine if the fill light is doing its job, you need to evaluate it from the camera position. Check to see if the fill light is casting a shadow of its own by looking through the viewfinder. In loop lighting, the hair light and background lights are used the same way they are in Paramount lighting.

Rembrandt Lighting. Rembrandt or 45-degree lighting is characterized by a small, triangular highlight on the shadowed cheek of the subject. It takes its name from the famous Dutch painter who used window light to illuminate his subjects. This lighting is dramatic and more often used with masculine subjects. Rembrandt lighting is often used with a weak fill light to accentuate the shadow-side highlight.

This is a beautiful image made with a single softbox and no fill. The lighting is true Rembrandt-style with a perfect triangular highlight on the shadow side of her face. Note, too, the elegant posing of the hands. Photograph by Cherie Steinberg Coté.

This is a beautiful image made with a single softbox and no fill. The lighting is true Rembrandt-style with a perfect triangular highlight on the shadow side of her face. Note, too, the elegant posing of the hands. Photograph by Cherie Steinberg Coté.

For Rembrandt lighting, the main light is moved lower and farther to the side than in loop and Paramount lighting. In fact, the main light comes almost from the subject’s side, depending on how far his or her head is turned away from the camera.

The fill light is used in the same manner as it is for loop lighting. The hair light, however, is often used a little closer to the subject for more brilliant highlights in the hair. The background light is in the standard position.

With Rembrandt lighting, kickers are often used to delineate the sides of the face. As with all front-facing lights, avoid shining them directly into the lens. The best way to check for this is to place your hand between the subject and the camera on the axis of the kicker. If your hand casts a shadow on the lens, then the kicker is shining directly into the lens and should be adjusted.

Split Lighting. Split lighting occurs when the main light illuminates only half the face. It is an ideal slimming light. It can also be used with a weak fill to hide facial irregularities. Split lighting can also be used with no fill light for dramatic effect.

In split lighting, the main light is moved farther to the side of the subject and lower. In some cases, the main light may be slightly behind the subject, depending on how far the subject is turned from the camera. The fill light, hair light, and background light are used normally for split lighting.

Cherie Steinberg Coté photographed this unusual bridal veil, and hat. Because of the size of the hat, the rounded softbox was lowered to a little above face height, producing a hybrid split lighting. The close proximity and softness of the light caused the light to wrap around the contours of the bride’s face with no shadow edges. The position of the main light and the turn of the head dictates the type of lighting pattern that will be produced.

Cherie Steinberg Coté photographed this unusual bridal veil, and hat. Because of the size of the hat, the rounded softbox was lowered to a little above face height, producing a hybrid split lighting. The close proximity and softness of the light caused the light to wrap around the contours of the bride’s face with no shadow edges. The position of the main light and the turn of the head dictates the type of lighting pattern that will be produced.

In this exceptional image by Dan Doke, the bride was lit with a modified profile-lighting pattern. The head was not fully turned in the traditional profile pose and, as a result, the main light is not a true backlight, although it is behind the bride.

In this exceptional image by Dan Doke, the bride was lit with a modified profile-lighting pattern. The head was not fully turned in the traditional profile pose and, as a result, the main light is not a true backlight, although it is behind the bride.

Profile or Rim Lighting. Profile or rim lighting is used when the subject’s head is turned 90 degrees away from the camera lens. It is a dramatic style of lighting used to accent elegant features. It is used less frequently now than in the past, but it is still a stylish look.

In rim lighting, the main light is placed behind the subject so that it illuminates the profile of the subject and leaves a polished highlight along the edge of the face. The main light will also highlight the hair and neck of the subject. Care should be taken so that the accent of the light is centered on the face and not so much on the hair or neck.

The fill light is moved to the same side of the camera as the main light and a reflector is used to fill in the shadows. An optional hair light can be used on the opposite side of the main light for better tonal separation of the hair from the background. The background light is used normally.

ADAPTING THE FORMAL LIGHTING PATTERNS TO SUIT THE SITUATION

While the basic lighting patterns do not have to be used with absolute precision, it is essential to know what they are and how to achieve them. If, for instance, you are photographing your bride and groom outdoors, you can position a single main light to produce the desired lighting pattern and ratio, then use the ambient light (shade or backlighting) as the fill light. No other lights are needed to produce every one of the five basic portrait lighting setups. The use of reflectors, instead of an independent fill light or kickers, may accomplish much the same results in terms of controlling light.

You can also create an elegant profile of the bride with a single flash used as a backlight, outlining the edges of her face, neck, and the wedding veil. With the daylight as fill, only one light is required to produce an elegant, classically lit portrait.

Buy this book from Amazon

Today's post is an excerpt from the book Tucci and Usmani's The Business of Photography, by Damon Tucci and Rosena Usmani. It is available from Amazon.com and other fine retailers.Once in a while, we have we have been fortunate enough to photograph celebrity clients. I have photographed sports legends Marshall Faulk and Horace Grant and one of the Backstreet Boys, Howie Dorough. I have also been fortunate enough to photograph some ostentatious, million-dollar events. These events can be very exciting, and they can also be very lucrative. They require a totally different mind-set. The stakes are higher, and so is the pressure. Perform well on the right one, and that can be your ticket in to the rich and famous. Fall on your face, and you’ll never work in this town again.Here is how I have tackled such events: When doing these large jobs, the lead photographer must perform almost as a director. I employ a team of four or more. I am fortunate to have been in this business for a while, and I have a large pool of friends/colleagues I can call on to form the dream team for these events. Our fees are upward of $20,000 for these types of events. That gives us the budget to staff accordingly.

It’s better to have more hands on deck than less.There are a lot of balls to juggle when you are working these events. There are many times when important events are simultaneously going on in different locations. Typically, I stick to the bride and have other staff members photograph the group, capture detail shots, etc.

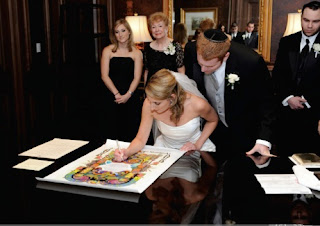

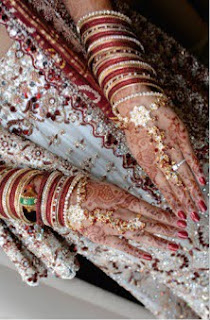

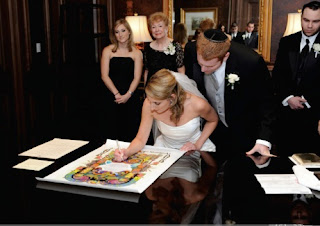

Let’s not forget Indian and Jewish ceremonies. The largest, most lucrative events I have photographed were Indian andJewish events. Indian events are a wonderful departure from traditional Christian ceremonies. The colors are vibrant, and the customs and rituals are fascinating. Indian weddings usually last three days or more and pay accordingly. Jewish weddings are rich in tradition. They are wonderful celebrations of life. The families are very close and, in my experience, they are a lot of fun. I love being in the middle of the hora with a fisheye lens on my camera—it’s like shooting a rock concert.Both of these events require a rudimentary knowledge of the cultures to capture them effectively. While I was working at Disney, they had a rabbi come in and teach the non-Jewish photographers about the important elements of a Jewish wedding. You can also find out a lot of information online or check out Photographing Jewish Weddings (Stan Turkel; Amherst Media, 2009). My experience with Indian events was a little different. A young couple came to me for my contemporary style.

Many mainstream Indian photographers are very traditional in their approach. They tend to cater to the parents rather than the bride and groom. Anyway, I explained that I knew little about their culture but was up for the challenge. They assigned me a family member to help guide me on the must-have shots.That was many Indian events ago. Eventually, I got the hang of it, even though in my experience all of the Indian events I have photographed are a little different.The bottom line is that both of these events are very lucrative and very enjoyable. Both cultures place a very high value on family and photographs. These are tight-knit communities, and if you do a great job for one of these clients, chances are you will be receiving calls from their friends soon.Buy this book from Amazon